Wine tasting and the biodynamic calendar part 2 - did I forget something?

Could it be that the biodynamic calendar only affects "natural" wines that are alive and not dumbed down with a lot of sulfites?

Did I forget an important factor in my previous post in which I concluded that there is no relation between perceived wine quality and the phases of the moon? Could it be that sulfites, filtration or stabilizion make wines taste the same on every day and rob them of the relationship with the moon? This is what a couple of commenters including wine writers Wink Lorch and Dennis Lapuyade suggested in response to an article by Jamie Goode. I see some grumpy old wine snobs already frowning because that concept sounds even more esoteric than Maria Thun’s calendar on its own. But let’s keep an open mind and find out.

Luckily, the data I analyzed includes wines from Foillard, Lapierre, Occhipinti and other producers who are known for their low-intervention style. So on top of the “Fancy Wine Effect”, the “Weekend Effect”, and the “General Biodynamic Calendar Effect”, I can also look at whether we see differences in scores depending on the moon specifically for “natural” wines.1

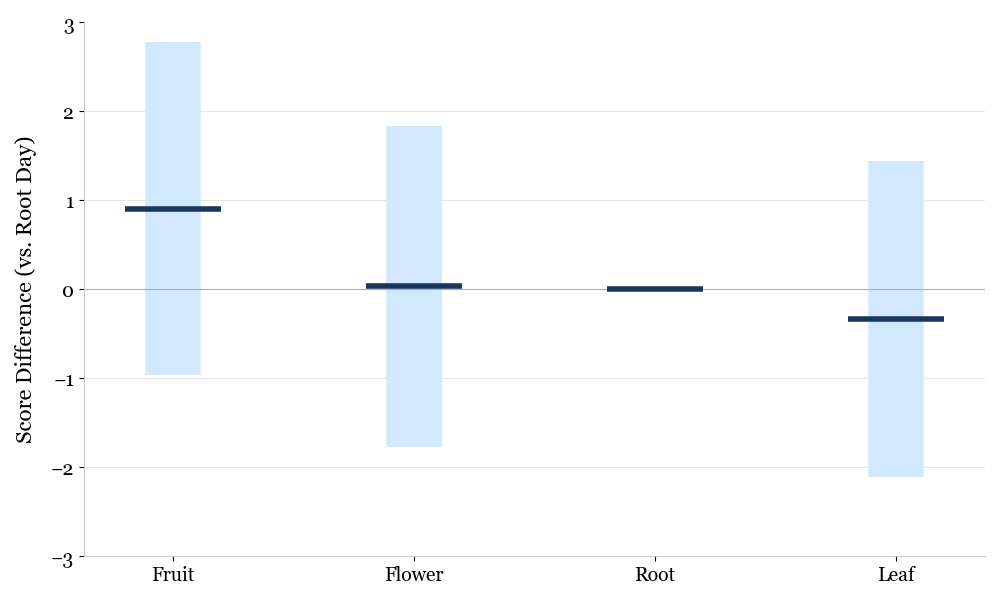

The results are pretty much the same: there is no statistically significant effect of the biodynamic calendar on wine scores, even when looking separately at natural wines. While at first sight the average score seems to be highest on Fruit Days, the difference is statistically indistinguishable from zero: the light-blue bars that visualize uncertainty clearly cross the zero line.2

Did I forget, anything else? To be sure, it’s always a good idea to check the literature and see what wine academics have found using carefully designed experiments. Compared with statistical analysis, the advantage of controlled experiments with expert tasting panels is that it allows the researchers to control for various confounding factors. The downside of course is the much smaller number of reviews and tasters.

The main experimental study on the subject of the biodynamic calendar and wine tasting was published already in 2017 by Wendy V. Parr and her colleagues (Parr et al, 2017). For their paper “Expectation or Sensorial Reality? An Empirical Investigation of the Biodynamic Calendar for Wine Drinkers,” the researchers had 19 professional wine tasters blind-taste the same Pinot Noirs multiple times on different days without knowing which were supposedly “favourable” or “unfavourable” days for tasting. The results showed that while the tasters’ perception varied across days, their preferences and descriptions had nothing to do with the biodynamic calendar. The punchline:

“The current study found no evidence to support the notion that wine tasters’ evaluations of a wine’s sensory attributes are influenced by the lunar cycle.”

Parr et al, 2017

Ultimately, the study suggests that if someone perceives a difference on Fruit Day vs Root Days, this is likely a “placebo effect” driven by expectation rather than any actual change in the wine’s flavor. We still have lunar permission to taste every day — we just shouldn’t check the biodynamic calendar beforehand to avoid that our mind plays tricks on us.

So what does affect our perception of a wine?

If the biodynamic calendar is not responsible, why does the same wine sometimes taste differently on different days? There are actually a number of reasons with more solid scientific backing.

Our body

We aren’t the same taster every day. Our mouth is a complex chemical environment, and even minor shifts in our biology can change how a wine lands on the palate. For instance, certain medications or a simple nutrient deficiency can tweak the composition of our saliva, making us more sensitive to bitterness. Also when saliva flow is reduced, for example due to dehydration, a wine can feel more astringent (Wang et al, 2024). Stress has been shown to actually dull our ability to perceive sweetness (Al’Absi et al, 2012). In general, taste sensitivity isn’t fixed. It fluctuates with hormone levels, which can lead to daily, monthly and seasonal patterns (Costanzo, 2024). And much like how everything in the grocery store looks delicious when you're starving, hunger also affects the taste of wine (Fu et al, 2021).

The world around us

It’s not only us, it’s also the world around us that affects our senses. Loud or rough noise can distract the brain, dulling the perception of sweetness and making the alcohol feel more prominent. On the flip side, the right music can act as "sonic seasoning," priming the brain to perceive a wine as more powerful or refreshing (North, 2012; Wang and Spence, 2017). The very air you breathe plays a role, too. Various studies have shown how humidity, air pressure and ambient temperature affect how volatile aromatic compounds escape the liquid and thus affect our taste perception (for example, Hummel, 2011 and Burdack-Freitag and Bullinger, 2010).

The tasting setup

Of course, as every wine lover knows, aromas depend quite heavily on the wine glass. The infamous champagne flute is fine for bland Prosecco, but you will not be able to enjoy the complexity of a special bottle of champagne. Also the order of tasting matters due to the so called carry-over effect: the taste of a previous wine influences our perception of the current one (Durier et al 1997). For example, if you move from a high-acid wine to a medium-acid wine, the second can feel somewhat flat. Any food you eat before or during the tasting has a strong effect as well. For example, proteins in meat can bind tannins and make a wine feel less astringent. Lastly, during a long tasting, sensory fatigue may set in, meaning that after repeated sips, your receptors may tune out and perceive a wine as less complex (Rolls et al, 1981).

The wine

And of course we shouldn’t forget that the wine actually might not be exactly the same from one tasting to the next. One bottle might have been filled from the top of a barrel whereas another one came from the bottom, leading to some batch variation. Furthermore, bottle variation might come from heat during transport, light on the shelf or an imperfect closure. So even when the bottle looks the same, it doesn’t mean that the liquid inside is exactly the same as during a previous tasting.

This long (and most likely incomplete) list nicely shows that taste perception is complex. There are a zillion factors that can explain why your favorite bottle might taste a bit off one day. So don’t blame the moon — try to relax with your favorite playlist, hydrate, grab a salty snack or simply switch your glassware. Science suggests that these tweaks have a much higher chance to improve your tasting experience than waiting for the next Fruit Day.

References

Al’Absi, M., Nakajima, M., Hooker, S., Wittmers, L. and Cragin, T. (2012) Exposure to acute stress is associated with attenuated sweet taste, Psychophysiology, 49(1), pp. 96–103.

Burdack-Freitag, A. and Bullinger, A. (2010) Odor and taste perception at normal and low atmospheric pressure in a simulated aircraft cabin, Journal für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit, 5(2), pp. 139–146.

Costanzo, A. (2024) Temporal patterns in taste sensitivity, Nutrition Reviews, 82(6), pp. 831–847.

Durier, C., Monod, H. and Bruetschy, A. (1997) Design and analysis of factorial sensory experiments with carry-over effects, Food Quality and Preference, 8(2), pp. 141–149.

Fu, O., Minokoshi, Y. and Nakajima, K.I. (2021) Recent advances in neural circuits for taste perception in hunger, Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 15, p. 609824.

North, A.C. (2012) The effect of background music on the taste of wine, British Journal of Psychology, 103(3), pp. 293–301.

Parr, W.V., Valentin, D., Reedman, P., Grose, C. and Green, J.A. (2017) Expectation or sensorial reality? An empirical investigation of the biodynamic calendar for wine drinkers, PLOS ONE, 12(1), p. e0169486.

Rolls, B.J., Rolls, E.T., Rowe, E.A. and Sweeney, K. (1981) Sensory specific satiety, Appetite, 2(2), pp. 103–121.

Wang, Q. and Spence, C. (2017) Assessing the influence of music on wine perception among wine professionals, Food Science & Nutrition, 6(2), pp. 295–301.

Wang, S., Smyth, H.E., Olarte Mantilla, S.M., Stokes, J.R. and Smith, P.A. (2024) Astringency and its sub-qualities: a review of astringency mechanisms and methods for measuring saliva lubrication, Chemical Senses, 49, p. bjae016.

Uncertainty, visualized by the size of the light blue bars is larger for natural wines because there are fewer natural wines in the sample. Thus, we can be less sure about out estimated coefficients.